Lending and the Civil Rights Movement

A major component of the American Dream is to grow wealth by owning and building equity in property. For most people, borrowing to purchase a home is the quickest and most basic route to achieving this dream. Although obtaining a home loan isn’t always easy, lenders’ decisions are usually based on factors that the borrower can influence or control. Ethical lenders look at the totality of a borrower’s situation to make their lending decisions. Factors such as the value of the property, the borrower’s ability to make payments, their past performance on other loans, and the borrower’s credit score all give a lender the information they need to make a sound lending decision based on the merits of the loan inquiry itself. When lenders base their lending decisions on other factors, such as a borrower’s color, race, sex, or national origin, they are not only acting unethically, they are breaking the law.

Unfortunately, this has not always been the case. Housing discrimination and segregation in the United States had already been a fact of life for African-Americans for decades, but the passage of the National Housing Act of 1934 aggravated this problem by further limiting the population’s access to mortgages through a process known as redlining.

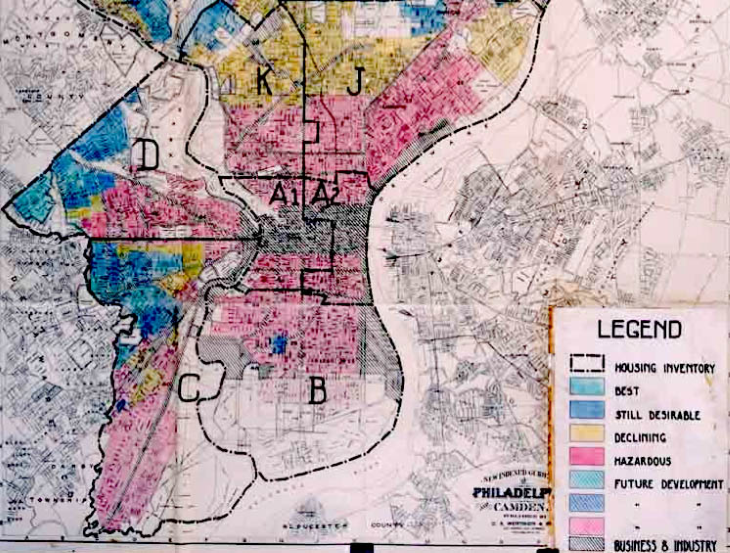

Beginning in 1935, the newly created Federal Housing Administration surveyed 239 cities throughout the United States and created “residential security maps” that indicated the desirability of residential real estate in a given area. Newer or well-established upper-class neighborhoods were outlined in green or blue to indicate that the property was safe for investment, while minority neighborhoods were outlined in red and designated as “hazardous” for investments. (Neighborhoods bordering the redlined areas were outlined in yellow, labeled “definitely declining,” and were also considered hazardous for lending purposes). Properties that were located in the red or yellow neighborhoods were not eligible for FHA mortgage insurance, making lenders reluctant to lend in the area and giving them official cover against charges of discrimination.

Redlining dried up the credit that was available to borrowers in outlined areas making it difficult for neighborhoods to attract homeowners and accelerating the process of urban decay in the heart of American cities. African-Americans and other minorities became trapped in the inner cities of America where there were fewer and fewer economic opportunities. The effects of this policy have had far-reaching consequences that are still with us today.

Starting in the 1940’s, the Civil Rights Movement was a concerted effort by African-Americans to correct these types of wrongs by securing constitutional rights for all Americans, regardless of color, race, sex, or national origin. Among the movements many achievements, one of the most important was securing the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act. This act makes it illegal for lenders or landlords to make credit and housing decisions that discriminate against anyone due to race, color, religion, or national origin. (Later amendments to the act added sex and familial status as protected classes in 1974 and 1988, respectively).

While the Fair Housing Act didn’t cause an immediate change to the practice of redlining, it gave civil rights activists an important tool to use in the fight to roll back redlining’s effects on America’s minority neighborhoods. Beginning in the 1970’s, community organizations began using the Fair Housing Act and similar laws as the basis for lawsuits against banks and other lending institutions. This exposed companies that continued to redline and led to the passage of additional laws, such as the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, aimed at ending the practice.

Today the ability to pursue the American dream through property ownership is more of a reality than it has ever been thanks to the efforts of the Civil Rights Generation. Regardless of our own race, color, religion, or national origin – we owe them a debt of gratitude for their service on our behalf.

Let us help you fund your next project

We provide mortgage loans with lower interest rates, higher LTVs, longer terms, and lower fees for properties that are difficult to finance.

Contact Us

(877) 589-7533 LoanOfficers@NotSoHardMoney.com

E. Paul Whetten

Paul Whetten is the Managing Executive of American Life Financial, a private money lender based in Mesa, Arizona. He has 10 years of experience in enterprise management and small business accounting, and over 14 years of experience in the financial services industry. Paul holds a Master’s degree in Administration from Northern Arizona University and is an adjunct professor of business at Mesa Community College.